Ultrasound FInding

The left lung was hyperechoic and enlarged. The heart was displaced to the right, compressed, and consequently small. The right lung was compressed and hypoplastic. Hydrops was present, secondary to cardiac failure, manifested by bilateral pleural effusions, mild ascites, and generalized subcutaneous edema.

Compression of the heart and the great veins draining into the right atrium (SVC and IVC) likely contributed to the reduced cardiac size, decreased venous return, and diminished stroke volume, ultimately resulting in cardiac failure and hydrops.

Discussion

The differential diagnosis for echogenic areas in the fetal chest includes congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH), cystic adenomatoid malformation (CAM), pulmonary sequestration, and tracheal or bronchial atresia.

King et al., in their review of echogenic lung lesions detected by prenatal sonography, reported correct prenatal diagnoses in 13 of 17 fetuses with echogenic lung masses.

Therefore, a definitive prenatal diagnosis of bronchial atresia may not always be possible.

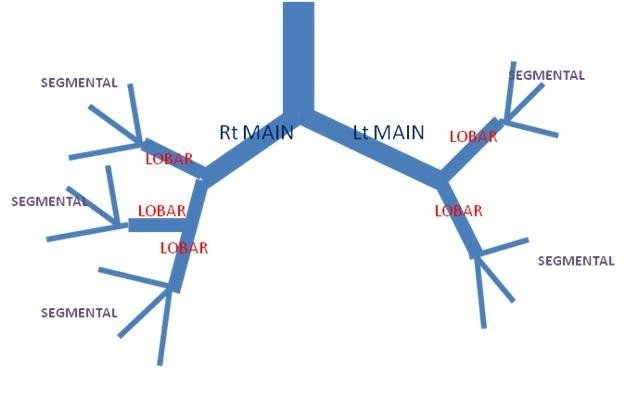

Bronchial atresia can affect the main bronchi, lobar bronchi, or segmental/subsegmental bronchi.

Congenital bronchial atresia is a rare anomaly resulting from focal obliteration of a main, lobar, segmental, or subsegmental bronchus. It most often affects segmental bronchi at or near their origin.

The airway develops systematically: lobar bronchi appear in the 5th week, subsegmental bronchi in the 6th week, and distal bronchioles in the 16th week of fetal development. In bronchial atresia, although the lung tissue distal to the atretic bronchus lacks communication with the central airways, the development of distal structures is usually normal.

This supports the theory that bronchial atresia results from an antenatal vascular insult leading to atresia of a main, lobar, or segmental bronchus after the 15th intrauterine week. Schuster et al. reported that the bronchial pattern distal to the stenosis is entirely normal, suggesting that the atresia is not a result of abnormal growth and development but rather a focal effect secondary to a traumatic event during fetal life.

Raynor et al. described cases of secondary bronchial atresia caused by a mucosal flap, hypertrophy of the bronchial mucosa, bronchial kinking (secondary to herniation), or external compression of bronchi by abnormal vascular formations, such as a patent ductus arteriosus or a pulmonary vein aneurysm.

A poor antenatal outcome is associated with mainstem bronchial atresia rather than lobar atresia. Accurate determination of the level of obstruction may not be reliably possible on antenatal sonography. Even lobar bronchial atresia can present as a large, seemingly lung-filling, echogenic pulmonary mass with significant mediastinal shift and diaphragmatic eversion.

Hadchouel et al. noted that distal bronchial atresia is an etiology for hyperechoic lung lesions and that the natural history of such lesions is generally favorable. Therefore, termination of pregnancy is not automatically necessary in suspected bronchial atresia.

POST NATALLY

In the newborn, bronchial atresia may appear as a water-density mass on chest X-ray, representing fetal lung fluid trapped behind the atresia.

During childhood, this fluid typically dissipates, and bronchial atresia is then often identified due to focal air trapping. The short atretic segment can lead to mucus accumulation within the distal bronchi, forming a bronchocele and resulting in underventilation of the affected lung region.

In adults, bronchial atresia is often characterized by a solitary pulmonary nodule on imaging, corresponding to a mucus plug. The bronchocele may contain an air-fluid level. The distal lung may be emphysematous, creating an area of hyperlucency surrounding the affected bronchi.

This abnormality is frequently an incidental finding (approximately 50% of cases), often in young men, and is generally asymptomatic.

References

1)Kassanos D, Christodoulou CV, Agapitos E, Pavlopoulos PM, Pagalos N .Prenatal ultrasonographic detection of the atresia sequence. Ultrasound Obstetric Gynecol 1997; 10: 133-6

2)Ramsay BH, Byron FX. Mucocele, congenital bronchiectasis, and bronchogenic cyst. J Thorac Surg. 1953;26(1):21-30.

3)Jederlinic PJ, Sicilian LS, Baigelman W, Gaensler EA. Congenital bronchial atresia. A report of 4 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1987;66(1):73-83.

4)Kinsella D, Sissons G, Williams MP. The radiological imaging of bronchial atresia. Br J Radiol. 1992;65(776):681-685.

5)Poupalou A, Varetti C, Lauron G, Steyaert H, Valla JS. Prenatal diagnosis and management of congenital bronchial stenosis or atresia: 4 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):e11-4.

6)Griffin N, Devaraj A, Goldstraw P, Bush A, Nicholson AG, Padley S. CT and histopathological correlation of congenital cystic pulmonary lesions: a common pathogenesis? Clin Radiol. 2008;63(9):995-1005.

7)Schuster SR, Harris GB, Williams A, Kirkpatrick J, Reid L. Bronchial atresia: a recognizable entity in the pediatric age group. J Pediatr Surg. 1978;13(6D):682-689.

8)Raynor AC, Capp MP, Sealy WC. Lobar emphysema of infancy: diagnosis, treatment, and etiological aspects-collective review. Ann Thorac Surg. 1967;4:374.